A couple of months ago Jean M. Twenge published a Substack newsletter entitled “Are books dead? Why Gen Z Doesn’t Read.”

We all know why Gen Z doesn’t read and why we all read less than ever before, but this piece is well worth a review – the data showing that, “coincidentally,” reading as a behavior began to decline precipitously right around the time of the rise of the mobile internet and mobile social media, the early-2010s. We all read less because of our devices and Gen Z especially reads less because in many cases devices are all they’ve known as a means for occupying downtime.

It’s downtime reading or “reading for pleasure” which Twenge’s piece primarily focuses on as she repeatedly and effectively makes the point that we all read for pleasure less now and Gen Z reads for pleasure less than any previous modern generation. The overall point of her piece, as I take it, is that as we collectively forget how to read to occupy downtime we’re likely undermining ourselves in some pretty critical ways. As she puts it, “In particular, reading long-form text, including books, is necessary for success in college, graduate school, and in many jobs. It’s also useful for understanding politics, policy, and parenting.” The less we read, the less capable we become. Period.

This is obviously concerning.

I hope we can agree that reading is a healthy behavior. We now know that the most critical variable determining whether a person has an unhealthy relationship with social media is not what they do on social media but simply how much time they spend in those “spaces.” I wonder whether the opposite might be true of reading. I wonder if we could safely conclude that reading, almost regardless of what is being read, is a fundamentally healthy behavior, one which you’d be glad to hear a friend or loved one is regularly taking part in.

What would we need to be able to say about reading in order to come to such a conclusion? I think that like most things it could probably be boiled down to a question as simple as this: Does reading (almost anything) tend to leave the average reader in a better or worse state when the reading is completed?

Unless you’re trying to be difficult, I think you’ll acknowledge the broad truth here. The act of reading is almost always harmless at worst while we can now convincingly argue that social media is almost always harmful.1 In The Anxious Generation Jon Haidt stresses the importance of considering not just the cost (dependence, isolation, anxiety, addiction, etc.) of giving a kid a phone-based childhood but also the opportunity cost of such an approach. The idea is that when a person adopts a phone-based lifestyle they simultaneously engage in unhealthy behaviors while surrendering the opportunity to engage in far healthier behaviors. It’s a double loss.

For our purposes, of course, I’ll ask you to consider the opportunity cost of a child choosing to sit on social media rather than reading a book or magazine. By sitting on social media rather than reading, we know they’re engaging in unhealthy behaviors that could lead to serious mental health issues. But what are they also potentially losing out on through this choice?

I’m not an idealist and I don’t think I’m an idiot. Before we continue I want to make it clear that I do not think we could ever successfully elevate reading over electronics use as an alluring downtime activity for young people or any group anymore. That ship has sailed and for me at least it sailed long before the invention of handheld electronics. Television won from day one. Reading lost out to TV for the same reason it has lost out to social media. It’s boring! For me, reading almost anything can be intensely boring. I’m pretty sure millions of American adolescents are with me on that one and I’m a former English teacher and the son and grandson of English professors and I feel no shame in stating that a boring activity is boring.

Reading is boring. For (probably) the majority of us, it just is. And yet, prior to the advent of handheld electronics, far more of us turned to this boring activity with regularity as a means for occupying downtime and even as a source of pleasure. This was true of kids, even, and it’s likely all of us can recall this attitude towards reading being explicitly taught in our schools.

I grew up on Sustained Silent Reading. I can’t remember how it went every year but my recollection is that for most of my public schooling experience in Colorado Springs School District 11 we did some kind of sustained quiet reading in some class nearly every day, especially through middle school, and then as English classes became more advanced at the high school level, we were frequently given time to read class texts in class (or given more time to read books of our choosing).

The educational methodology behind Sustained Silent Reading or just the idea of giving kids time to read in class is simply that, by reading almost anything, kids become more proficient readers and more proficient readers are better students. That was and likely still is the academic motivation and explanation for requiring students to read quietly in class and the logic seems straightforward enough, it requires no discussion. What may be worth discussing, though, are the other common benefits conveyed by the act of reading to regular readers.

Not only is regular reading likely to produce stronger students with better grades, it’s also likely to produce calmer, happier, better-rested students with better habits. This is all very simple.

We now openly acknowledge that the social media apps most people blast their brains with (all day) each day directly contribute to anxiety, depression, sleep-deprivation, etc., especially for kids. This is how embarrassingly low we’ve set the bar for our downtime amusement in 2024 - through our phones, most of us now actively contribute to our own mental health issues (suffering) through an optional leisure activity whose actual benefits are incredibly hard to identify if they exist at all.

Social media and other compulsive phone behaviors (gaming, binge-viewing, binge-listening) make students less calm (more anxious, unhappy) and more sleep-deprived while enabling the formation of myriad bad habits, some of which are extremely serious.

Social media and other compulsive phone behaviors are therefore dangerous for kids.

Reading, on the other hand, is boring.

One leisure activity is alluring but is dangerous and destructive. The other is generally boring but has no negative side effects and in fact its effects are generally, overwhelmingly salutary. I wonder which of these activities we should be actively promoting in our public schools (while openly discouraging participation in the other as an obvious harm to children).

This is a tough one.

I don’t mean to suggest that schools have ceased to promote reading. Reading remains the central activity and basis for nearly every academic class, I assume, and my third-grade daughter is constantly participating in various “reading challenges.” It’s clear that the educational world still sees great value in reading. What I think many educational leaders never realized or even considered, though, was that, through their failure to discourage destructive phone/electronics use as a default downtime activity, they effectively contributed to the elimination of the idea of reading as a healthy (non-destructive) way to occupy one’s free time. The more kids have been allowed to fill in-between time with screens, the more their brains have come to expect to fill in-between time with screens. Just like us adults.

I’ve already told you that screens defeated reading for me long ago. Television beat reading because for me it was a consistently less boring activity and one that I could engage in while completing other tasks like homework or sorting baseball cards. For me, the idea of “reading for pleasure” is almost laughable. For the most part, I just can’t do it.2

There are two sets of circumstances under which I am able to calm myself down enough to sit and read a book:

I’m by some water. If I’m at the beach or by a creek I can read all day. It’s always felt like what I’ve “needed” in order to read is for something to be occurring in the background so that I don’t feel trapped by the silence of sitting and reading. Moving water and ambient human sounds have always helped me settle into a book. This is why I’m extremely lucky there’s a bodacious fountain in the park I regularly sit in while at work. I can read by that fountain just like I can read by Lake Michigan.

I’m obligated to do the reading. Whether I have to read something for work or for some form of schooling, I can definitely read when I have to and - critically - I’m almost always glad for it.

Let’s assume for our purposes that most modern kids are a lot like me in that they struggle to read for pleasure in large part because they find it boring and, like me, they may have a sort of fear of the amount of silence represented by reading. If this is true of many or most kids, then reading challenges and pro-reading PR campaigns will never succeed in retaking the ground reading lost to electronics in the early-2010s in particular.

For now, in fact, it may be wise for us to put the idea of promoting “reading for pleasure” aside entirely. It may be more useful for us to begin to consider the ways in which we could promote “reading for survival.”

Here’s the logic:

However boring it may be, regular reading produces calmer, happier, better rested kids with better habits.

Compulsive phone use produces anxious, unhappy, sleep-deprived kids with bad habits.

The lifestyle and habits conferred on kids by compulsive phone use are destructive and unsustainable.

Unsustainable means “not capable of being prolonged or continued.” I use this word here to suggest that if our kids continue to live phone-based lives, we will break. The suggestion is that if everyone is living unsustainably society as we know it becomes unsustainable, period. It cannot survive. How could it?

The lifestyle and habits conferred on kids by regular reading are healthy and sustainable. These habits benefit both the reader and the society to which the reader belongs.

Wouldn’t it be logical to attempt to help (save?) our children en masse by discouraging the addictive, destructive, unsustainable behavior while promoting the healthy, constructive, sustainable behavior?

I doubt many would disagree with the logic here. It does make sense, primarily because intellectually this is not at all complicated. We’ve all always known that “reading is good” and I also believe that way more of us than you would think have always known that there’s something fundamentally wrong with this phone life. All you have to do to conclude that reading is fundamentally good is observe a reader. How do they look? How does it feel to be around them while they read? How do they act after they’ve been reading?

Now ask the same questions about a person, perhaps a kid, who’s been glued to TikTok or Instagram for 90 minutes.

. . .

. . .

So a solution is sitting right there for us. It is definitely not the solution, but it is a solution. By replacing some phone time with reading time we could replace a destructive, unsustainable behavior with a healthy, sustainable behavior. If we could encourage this shift at the system level, we could begin to loosen our collective dependence on electronics and promote greater overall child and adolescent (and societal) mental health. It all makes sense.

Yes it makes sense. But.

But.

But reading is boring. Sure it’s healthy. So is broccoli, so is running on a treadmill. Eating broccoli is a chore and so is reading. It’s boring and it’s so boring and kind of difficult that on a depressingly real level I would rather continue to engage in my unsustainable phone behaviors and to rationalize them and to make excuses around them than to work to replace them with a behavior I essentially know with absolute certainty would be better for me and my family and society overall.

It’s my thinking represented by the italics above. That’s my attitude towards reading and towards the other embarrassing deals I’ve made with myself over the years. I acknowledge that on some level I’ve always engaged in behaviors I recognize as unsustainable and as less healthy - in some cases dramatically so - than obvious alternatives. I also think I am far from alone in this regard and that without making excuses it’s probably fair to say that behaving irrationally and even self-destructively is to an embarrassing extent simply to behave like a human.

It is therefore human nature and our most basic inclinations - towards ease and away from difficulty, for example - which have led me to conclude that reading for pleasure has taken a permanent backseat to viewing or gaming for pleasure within our culture. But.

But . . . So what?

So what if reading for pleasure is dead or dying?

Just because reading for pleasure is dead or dying doesn’t mean we should abandon reading for all sorts of other reasons, perhaps our spiritual survival among them. This is a case where why we do what we do matters far less than whether or not we do it. If reading has no concerning side effects and as such represents almost the perfect opposite of and antidote to social media then as a society we should be promoting reading primarily not as a means for getting good grades or for broadening one’s understanding of the world but as a way to feel consistently better (less awful) about life and people and the future.

Phones make people and especially kids unhappy and they make people who were already unhappy more unhappy.

Reading a book might make a person bored at worst and - as an activity - it is extremely unlikely to create or deepen despair, especially across populations.

So when it comes to mental health, I think we can say this: Phones are bad, books are good.

If our public schools actually care about their students’ mental health, then, they should logically be constantly promoting reading (and exercise and simply being outside) as a healthy behavior while discouraging phone use as an unhealthy behavior. This is incredibly simple and it’s only logical.

For the few administrations brave enough to actually ban phones, I believe there is no choice but to grapple with this logic directly.

It’s not enough to simply take their phones away. Many kids may do alright with such a cold turkey approach - kids are far more resilient (anti-fragile!) than we give them credit for - but they might all benefit from the introduction of an alternative activity to help occupy their minds and fill their time.

This will be of particular concern to schools like the Des Moines secondary schools which utilize Standards Referenced Grading. Here’s what I said about Standards Referenced Grading in another post:

DMPS insiders will have noted an unaddressed elephant in this room. That elephant is called Standards Referenced Grading (SRG) and it has arguably been equally disastrous (as phones) to the educational environment within DMPS. For those who don’t know, SRG is an aptitude-focused approach to education, where in order to earn grades students just have to show aptitude for certain skills. The idea behind SRG has always been to separate grades from behavior. This is not a bad idea at all, but in practice - at least within DMPS - SRG has not been good for most kids because within DMPS’ version of SRG there are no deadlines and the overall amount of work required by a given class is greatly reduced. The unintended result of all this was, in my experience, a huge amount of “down time” built into most kids’ days either because they simply chose not to work that day or week or month (no deadlines) or because they’d already done their work and there was no new work for them to move onto (greatly decreased overall workload). You can imagine, then, how DMPS students have tended to fill that down time. Phones. In my experience, SRG and the ever-presence of phones have sort of propped each other up in DMPS classrooms. SRG created too much downtime, phones filled the downtime, and that’s the rhythm we became accustomed to. Hoover AP Rob Randazzo told me this is a collective concern for Hoover staff - the fear that all of a sudden kids who are accustomed to sitting pacified on their phones all day will become behavioral issues when they realize there’s “nothing to do” but they can’t be on their phones. For this reason I’ve already recommended that Hoover modify its SRG model to require far more “daily work” out of students.

This is where we’ll attempt to close out this discussion, by considering the case of Hoover directly. I have told you that Hoover is a phone school - right now Hoover students can use their phones wherever and whenever they want on Hoover grounds. Hoover is also an SRG school. Right now Hoover students have no deadlines and loads of downtime.

Next year the phones will be gone but the downtime will remain. The thought of this has many Hoover staff members concerned. How will they actually fill this time?

You’ve read at the end of my footnote that from the start I recommended to Hoover administration that they seek to modify their approach to SRG so that they could begin to demand far more work from their students. The idea here is not to overload Hoover students with busy work simply to keep them pacified, nor is it to increase student workload in order to directly improve academic performance. The idea behind increasing the daily workload for Hoover students is the same as the idea behind promoting reading as an alternative to phone use - While completion of “daily” academic tasks such as journaling or crosswords or informal quizzes is unlikely to directly impact the rate of college acceptance for seniors, for example, the utilization of such assignments is also incredibly unlikely to have a negative impact on student populations, beyond mild boredom.

This is where we’re at. Because we invented and embraced a means for occupying all of our downtime destructively and unsustainably - and because we handed this way of life to our children, who had no choice but to adopt it - we now have to consider the ways in which we could un-train our kids and ourselves. We have to be willing to attempt to replace our destructive downtime behaviors with behaviors that are, at worst, boring. Busy work is boring but it’s better than social media. Reading is boring but it’s better than social media. These are easy and important points to make.

I have no actual power to advise Hoover or any school. If I had that power, though, I would stand by my initial suggestion and I would combine it with my present suggestion. I would recommend that Hoover find a way to give its students actual, meaningful academic credit in exchange for committed reading of print materials, especially books and I would recommend they offer this opportunity to earn academic credit for reading daily and in such a way that it could become habit-forming.

Within the DMPS version of Standards Referenced Grading, a student can receive no academic credit whatsoever for reading or journaling or for completing basic daily assignments. This is because reading and journaling and work completion are viewed and classified as behaviors and the whole goal of SRG was to separate academic grades from student behavior. As I told you in my footnote, this was a nice thought but it has not worked out. It turns out behaviors matter and when you stop teaching behaviors altogether everything starts to fall apart and fast.

Another behavior that DMPS threw out as irrelevant to academic evaluation was persistence, stamina. This one hit English departments in particular.

I remember the day we were told we could no longer teach novels. In her piece Jean Twenge notes that her high school-aged daughters don’t read full length books in their English classes. This is a nationwide trend but as I read this I wondered whether Twenge’s kids attend an SRG high school. She tells us that many English departments have abandoned teaching novels perhaps in response to shortened attention spans but also because short stories avail themselves to (aptitude-focused) stand-alone assessments far more readily than full novels. Novels represent entire academic units for English teachers and students. They require attendance, commitment, and often an ability to overcome boredom. But these - attendance, commitment, an ability to overcome boredom, etc. - are behaviors and DMPS sees no explicit value in teaching (vs. encouraging) these to kids (through books). So we were ordered to stop teaching novels and we listened. This was around 2016 or 2017.

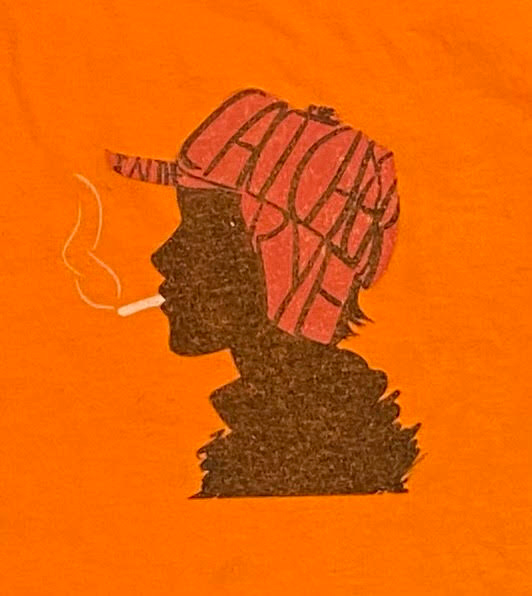

I took it hard, I remember. I’m embarrassed to say I even took it personally. It was the thought of never teaching Catcher in the Rye again that affected me most. God, I love Catcher. Many of my students loved it too and I enjoyed helping them learn to love it, to love Holden Caulfield.

I love Holden Caulfield. I definitely identify with him and probably always did. Holden is smart and sensitive and he feels like he fits in nowhere. I feel all that, you know I do. Holden is also a damaged kid. He’s been completely traumatized by the death of his brother Allie just as, as a kid, I was destroyed by the death of my best friend Blaine.

I remember about ten years ago I made my father and myself matching shirts that read “I hardly didn’t even know I was doing it, and you didn’t know Allie.” In the part of the book this quote comes from, Holden is describing his reaction to Allie’s death. He punched out all the windows in the garage. He was so upset, blind with grief, that he hardly knew he was doing it. But you wouldn’t understand anyway, he suggests (to the reader, directly!), because you didn’t know Allie.

I understood though. I didn’t know Allie but I did know Blaine.

I always cry when I read this quote. I just revisited it to make sure I quoted it properly and I cried. In these moments I think part of me is definitely crying over Blaine, over the ways in which I relate to Holden losing his beloved brother. That is there. What’s crazy, though, is I know that I’m also crying for Holden in these moments. I’m moved to tears by a fictional emotional experience concocted by the mind of an author who ultimately proved to be an anti-social pedophile. Salinger’s deeply problematic bio aside, what he did with Holden Caulfield is . . . over the course of an entire novel . . . he brought a character to life in such a way that many of us experience him - Holden - as an actual fragile person we feel deep sympathy and love for. (I want to jump into the book and protect Holden, every time.) He also accomplishes the same in far fewer pages through his depiction of Holden’s incredible kid sister, Phoebe. God I love Phoebe . . .

I do wonder, as many English teachers have over these recent years, whether a reader can feel the same sort of connection to a character in a short story. I don’t think it’s impossible but it’s likely far less probable. Novels can create entire worlds and involve us, the readers, in those worlds. They don’t always do this but they can and when it happens it can feel magical and meaningful. I think it’s fair to say that short stories are far less capable of accomplishing this and I also think it’s fair to say that social media is completely (utterly) incapable of accomplishing anything like this. So as we abandon the teaching of novels in favor of short stories, it’s understandable for teachers and others to wonder about all that we might be surrendering in the process.

I’m a former English teacher and the son and brother and nephew and grandson of English teachers. I clearly care about all the abstract and high-minded ways in which novels matter3, but I think conversations like that can be suspended indefinitely while we deal with the more pressing question which is: Can reading as a behavior be employed to counter-act the negative effects of the obviously destructive behaviors promoted by a phone-based life?

The answer is obviously yes. The trick will be to incentivize the boring (healthy) behavior while de-incentivizing the “fun” (destructive) behavior. What incentives do schools actually have to offer? In the end it always comes down to grades.

If phone schools like Hoover want to fully help their students confront and overcome the phone issues that have diminished their lives, then they will likely have to find the courage to reward positive behaviors with positive academic grades. This may require many administrators to admit that their grading systems are flawed and that they have made mistakes beyond allowing phones in classrooms. For this reason I don’t expect any of these things to happen but I feel that all of this was worth noting at this time.

Notes:

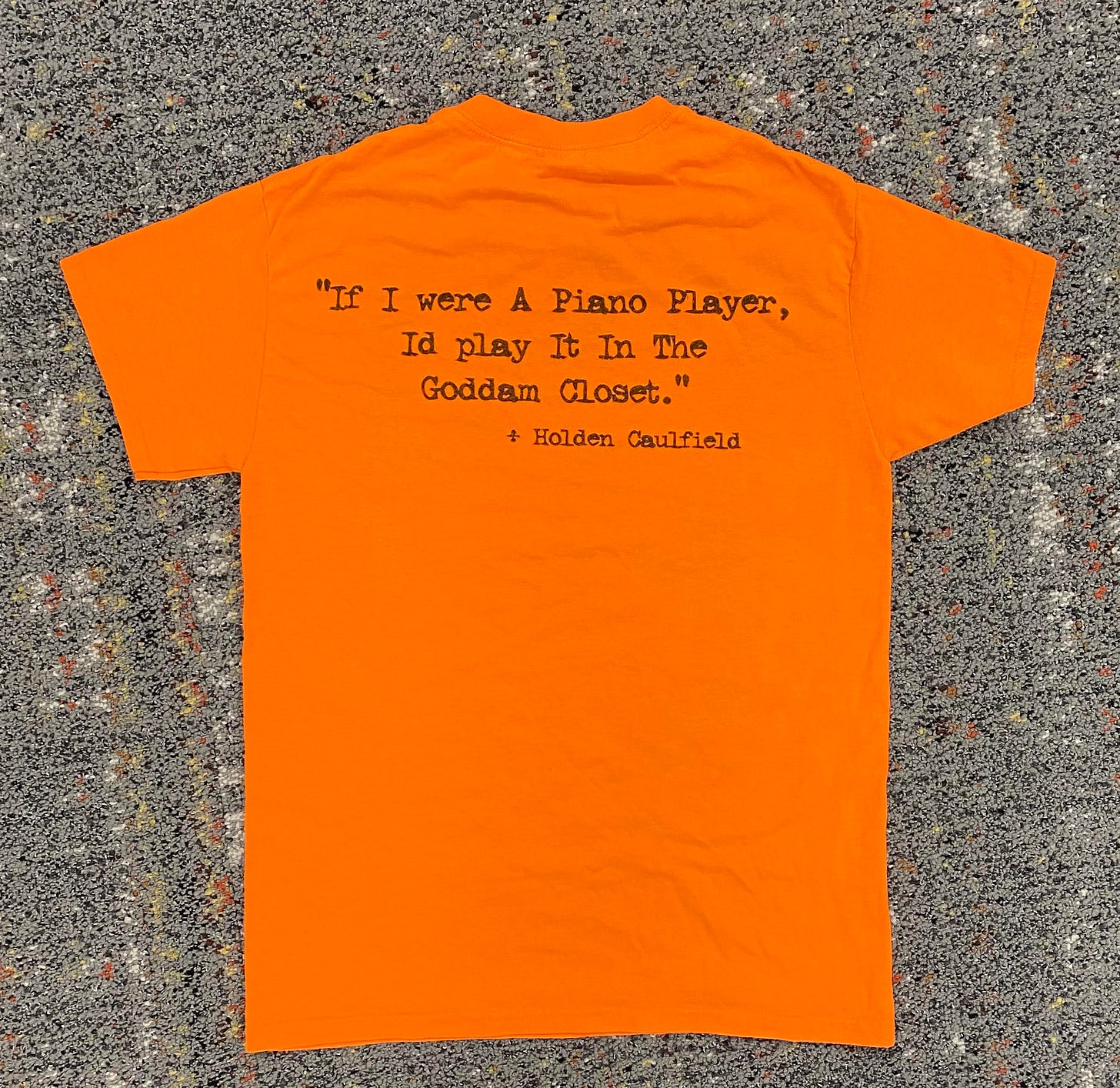

I can’t remember when exactly I last taught Catcher in the Rye. I do believe it was 2015 or 2016. I remember I had a great group of juniors that year though I have forgotten all their names. I felt especially connected to one particular class and after our Catcher unit they made me an amazing t-shirt, the front of which is the title image for this post. Here’s the back:

This is my other favorite quote from the book. We talked about this one a lot in class. Here Holden is criticizing the piano player at a New York nightclub. He feels that the pianist is far too showy and demonstrative. Holden of course thinks this man is a “phony” and he believes - as I do! - that if you’re an actual artist you should be almost completely unconcerned with who is observing you or whether you’re being observed at all.

A couple of thoughts this quote brings to mind:

Holden’s head would have exploded if he were real and if he were transported to the year 2024 in any civilized country. He’d rightly call us all phonies and he’d wonder whether anyone ever even thought to play a piano in a closet anymore.

I never got around to the subject of sleep. Another incredibly simple, non-philosophical way in which reading is good for us is that it puts us to sleep! I’m serious. I always used to read myself to sleep as a kid and as a younger adult. Then I replaced reading with documentaries and my sleep has suffered. Considering how far we’ve fallen - how obviously destructive nearly anything a kid does on a phone is - we should be glad to have students fall asleep while reading in classes rather than watching them pass out to Netflix. Most of the kids I know either pass out to TikTok or TikTok + melatonin, every night.

Speaking of reading in college, college kids are obviously woefully under-prepared for college-level reading, especially the volume of reading expected by many professors. I deal with this at work all the time. This is worth noting for every reason but is especially noteworthy because so many of our students come from Des Moines Public Schools. DMPS kids don’t read very much in part because DMPS teachers have no authority to require DMPS kids to read very much. My impression is that professors are now having to ask themselves whether they’re assigning too much reading - this would be an example of schools adapting to (accommodating) bad habits rather than helping students to overcome them. This is pretty much the WHOLE story at DMPS over the last 13 or so years and it’s 100% likely that similar processes have been playing out in schools and colleges across the nation over this timespan.

This entire essay could just as easily have been about exercise or simply spending time outside. I hope it’s clear that all I’m really talking about is identifying healthy behaviors that have no or very few negative side effects and finding ways to incentivize youth participation in these behaviors while finding ways to de-incentivize youth participation in the most embarrassingly, obviously destructive “activity” mankind ever conceived of . . . social media.

I love Jon Haidt’s discussions of children as anti-fragile. Phoebe is anti-fragile and Holden sees this. As he watches her on the carousel at the end of the novel he says, “All the kids kept trying to grab for the gold ring, and so was old Phoebe, and I was sort of afraid she’d fall off the goddam horse, but I didn’t say anything or do anything. The thing with kids is, if they want to grab for the gold ring, you have to let them do it, and not say anything. If they fall off, they fall off, but it’s bad if you say anything to them.” I love this. I completely fall apart whenever I read this section of the novel as well.

Within the schoolyear that I left DMPS (2022-2023), the district formally re-introduced (re-allowed) the teaching of novels and long non-fiction. It’s worth noting, though, that these were books chosen by the district for specific reasons and teachers were and are required to teach these books utilizing specific materials and specific assessments paid for by the district.

As I typically try to do, I’ll invite you to apply a broad and encompassing understanding of the concept of harm as we consider the harmfulness of social media. It’s clear that in the worst cases social media can be disastrous for mental health and has the clear capacity to splinter our society socially and politically. These are the obvious harms. Some of the more subtle harms which I do believe apply to different degrees to most social media users most of the time are: wasting time, wasting energy, slow-creep cynicism, increased materialism, tribalism, increased superficiality, spiritual emptiness, etc.

I have a couple general thoughts on why this is the case, nothing conclusive. For one, I’m a boy. I like to do things more than I like to sit around. I’m a lifetime athlete and lover of projects, I really like to be outside and moving and I don’t feel right if I’m not doing that. I also can’t stand silence, especially indoor silence. I associate reading indoors with the idea of intense silence and on some level I associate deep silence with death. So I run from it. Seriously! :)

This thought makes me think about all the fighting over banning books in America over the last year or two. Like almost everything that’s happened in the last 15 years, this left me feeling outside the culture and seriously dismayed. What had me dismayed was how much people on either side seemed to care about banning books . . . at a time in history when no one reads and at a time when books - especially kids books - have almost no direct influence over the culture as compared to all other media. But adult social media culture was up in arms over this issue. I was sympathetic towards my older friends who had impassioned responses to books being banned because I could feel the “child of the 60s” in them. But, baby . . . this ain’t the ‘60s. Books mattered in the ‘60s. Let’s get people reading again period before we start worrying too much about what they do and don’t read.